Historic Places

Historic Places of Volcano Village

Dive into the stories of Volcano Village through the buildings and places that shaped its unique character. From early homes and community spaces to schools and postal services, these historic sites illustrate how people lived, worked, and connected in the village over time.

Cooper Center

Built in 1928, the Old Japanese School House is one of the last remaining one-room Japanese language schools in Hawaiʻi. It stands as a reminder of a time when immigrant families worked together to preserve language, culture, and a sense of belonging for their children in Volcano Village.

When it opened in 1928, there were almost 170 Japanese-language schools from Kauaʻi to Kona, started by families who wanted their children to learn traditional culture and language.

The school was founded by local residents who formed the Volcano House Japanese School House Association and raised funds with help from the wider community. Constructed on donated land along Kalanihonua Road, the modest wood-frame building served students of all ages, who gathered after public school to study Japanese language, writing, math, and customs together in a single room.

“It didn’t matter how old you were or what your skill level was, everyone was together,” said Meleana Manuel, who attended the school from the 2nd to 6th grade in the 1960s.

Beyond education, the school quickly became a community hub. Over the years it hosted weddings, parties, film screenings, church services, Boy Scout meetings, and dance classes. Additional residences for teachers were added in the 1930s, further rooting the site in daily village life.

The school’s story also reflects broader tensions in Hawaiʻi’s history. Japanese language schools faced increasing political pressure in the early 20th century, culminating in legal battles that reached the U.S. Supreme Court, which affirmed parents’ rights to educate their children in their native language. That progress was abruptly halted in 1941, when the school was closed following the attack on Pearl Harbor and its principal, along with many others, was interned for the duration of the war.

In a 1983 interview, the principal’s wife Teruko Shiotani recalled how neighbors were terrified of being detained themselves and kept their distance from the school.

“People stayed away,” she remembered, noting that hers was the only family in Volcano taken in this way. Yet even in that climate of suspicion, there were small acts of kindness. One neighbor, Mr. Takaki, continued to offer rides into Hilo for errands—quiet gestures of support that stood out during a painful and uncertain time.

The school reopened in the 1950s, though enrollment gradually declined as families sought to assimilate into American culture. In later decades, the building continued to serve the community through arts programs and local gatherings. Today, the Old Japanese School House remains a cherished landmark—quiet, sturdy, and full of stories that reflect Volcano Village’s resilience, generosity, and multicultural roots.

Historic Schools

Keakealani School

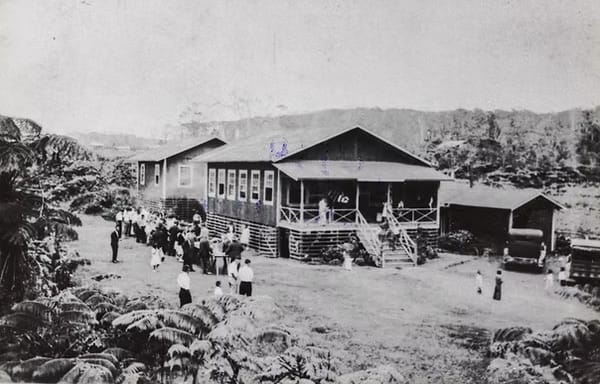

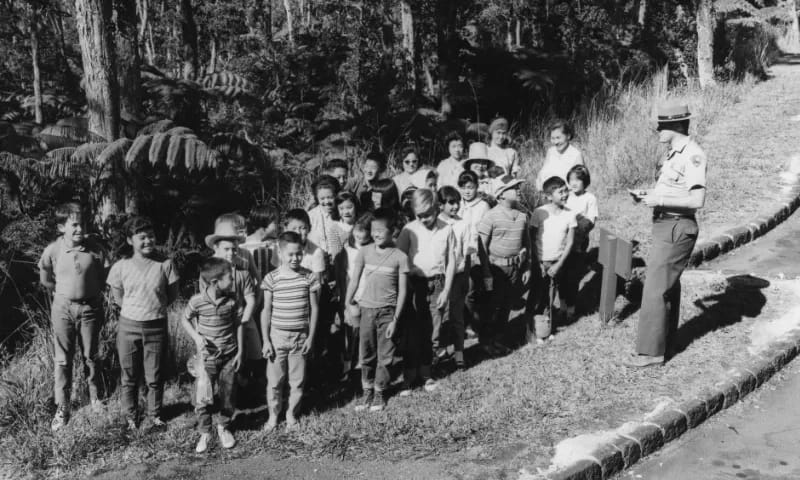

Keakealani School was Volcano’s first public school and opened in 1915 to serve a growing number of families settling in the area. Located on land donated along Haunani Road by entrepreneur Peter Lee, the one-room school educated students from first through sixth grade and was named after one of his daughters.

As the community continued to grow, the school was expanded in 1934 into the two-room, wood-frame building that still stands today. Former students remember its simplicity: two teachers, multiple grades in each room, and a weekly visit from the bookmobile.

For decades, it was the only school for nearly 40 miles, educating generations of Volcano children until students were transferred to Mt. View Elementary in 1973.

The building’s role did not end there. For more than 25 years, it served as an outdoor education center for students from across Hawaiʻi Island. In 2010, the site was returned to community use and became part of the Volcano School of Arts and Sciences, which continues to grow today. The historic schoolhouse remains at the heart of plans to expand the campus into a full K–12 facility, carrying its legacy of learning into the future.

Old Japanese School House

Built in 1928, the Old Japanese School House is one of the last remaining one-room Japanese language schools in Hawaiʻi. It stands as a reminder of a time when immigrant families worked together to preserve language, culture, and a sense of belonging for their children in Volcano Village.

The school was founded by local residents who formed the Volcano House Japanese School House Association and raised funds with help from the wider community. Constructed on donated land along Kalanihonua Road, the modest wood-frame building served students of all ages, who gathered after public school to study Japanese language, writing, math, and customs together in a single room.

“It didn’t matter how old you were or what your skill level was, everyone was together,” said Meleana Manuel, who attended the school from the 2nd to 6th grade in the 1960s.

Beyond education, the school quickly became a community hub. Over the years it hosted weddings, parties, film screenings, church services, Boy Scout meetings, and dance classes. Additional residences for teachers were added in the 1930s, further rooting the site in daily village life.

The school’s story also reflects broader tensions in Hawaiʻi’s history. Japanese language schools faced increasing political pressure in the early 20th century, culminating in legal battles that reached the U.S. Supreme Court, which affirmed parents’ rights to educate their children in their native language. That progress was abruptly halted in 1941, when the school was closed following the attack on Pearl Harbor and its principal, along with many others, was interned for the duration of the war.

In a 1983 interview, the principal’s wife Teruko Shiotani recalled how neighbors were terrified of being detained themselves and kept their distance from the school. “People stayed away,” she remembered, noting that hers was the only family in Volcano taken in this way. Yet even in that climate of suspicion, there were small acts of kindness. One neighbor, Mr. Takaki, continued to offer rides into Hilo for errands—quiet gestures of support that stood out during a painful and uncertain time.

The school reopened in the 1950s, though enrollment gradually declined as families sought to assimilate into American culture. In later decades, the building continued to serve the community through arts programs and local gatherings. Today, the Old Japanese School House remains a cherished landmark, full of stories that reflect Volcano Village’s resilience and multicultural roots.

The Village Post Office

For much of Volcano’s early history, getting mail was as informal as village life itself. Letters arrived by ship, were carried up rugged trails, and eventually left at Volcano House, where residents stopped by not just for mail, but to see neighbors and share news—an early hint of the post office’s role as a social hub.

As transportation improved, regular mail service followed. By the late 1800s, stage routes carried letters from Hilo to Volcano, with mail sorted at the Volcano House hotel under the watch of its famed manager, George Lycurgus. Even into the mid-20th century, villagers still picked up mail from local stores, sometimes finding unclaimed letters tacked to a wall by day’s end.

Concerns about access to the National Park eventually spurred residents to push for a post office of their own. In 1953, Volcano’s first village post office opened next to the Hongo store, with longtime resident Kazu Okamoto (who was new to postal work but deeply committed to the community) serving as postmaster for the next 37 years. What began with just 16 mailboxes soon grew as the village expanded.

The modern Volcano Post Office opened in 1978 amid celebration, marked by a maile lei blessing and community ceremony. With hundreds of mailboxes and a welcoming wooden design, it remains what it has always been: a place to collect letters, greet friends, and catch up on the daily life of the village.

“After all, without the post office where would we get to see all our friends and neighbors and catch up on all the latest news and gossip every day?”

— Virginia Dicks, Volcano newspaper columnist

Homes & Estates

ʻAinahou: The Shipman Estate

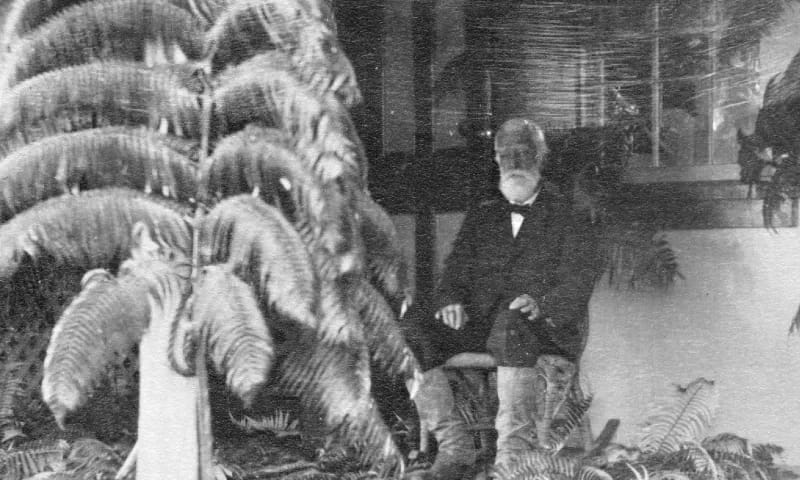

Businessman, conservationist, and philanthropist Herbert C. Shipman created ʻAinahou as a refuge during the uncertain years leading up to World War II. Located downslope from Kīlauea on land leased from Bishop Estate, the site offered both seclusion and safety, while remaining closely tied to Volcano Village.

From 1941 to 1971, Shipman developed ʻAinahou into a remarkable estate centered around a Craftsman-style home and lush gardens. Orchids, fruit trees, and rare plants from around the world thrived there, supported by an on-site nursery and innovative rainwater system. The property also played a pivotal role in saving the nēnē from extinction, when Shipman relocated the endangered birds to ʻAinahou in 1946.

The two-story ranch house was built of redwood siding and lava stone with influences from Adirondack and Japanese design. It served both as a family retreat and a working ranch. During the war years, cattle raised at ʻAinahou supplied meat to the military and later to Hilo markets, making the estate both productive and purposeful.

Today, ʻAinahou is recognized by the National Park Service for its historic integrity and strong connection to Shipman’s life and work. Though the property is now closed to the public due to limited resources and to protect wildlife, it remains an important chapter in the cultural and environmental history of Volcano.

Hale ʻŌhiʻa Tract

The Hale ʻŌhiʻa tract was one of Volcano Village’s earliest residential areas, developed in the early 20th century by plantation managers and other “summer people” seeking relief from the heat of lower elevations. Though now divided by Highway 11, the neighborhood still reflects the quiet elegance of its beginnings.

A walk down the narrow, tree-lined lane off Old Volcano Road is marked by two lava rock pillars and reveals a rare collection of homes from the 1920s and 1930s: plantation-inspired cottages, a craftsman bungalow, a manager’s home, a simple lanai-fronted residence, and one of Hawaiʻi’s earliest log cabins sit amid unusually large front yards. Even newer homes have been carefully designed to preserve the character of this distinctive historic enclave.

From plantation-inspired cottages and Craftsman bungalows to simple rectangular homes with protected lanais and some of the earliest log cabins in Hawaii, this narrow, tree-lined street is a living showcase of historic home styles.

Mr. Terry's Log Cabin - 1918

Mr. Terry, a teacher from Kamehameha Schools and leader of the Hilo Boys Club, is believed to have built the first home on the street around 1918. One log, carved with his name and dated 1901, hints that older materials were used. He constructed the cabin one log at a time with help from paniolo from the Shipman Ranch, who later used it as a way station. The rounded ʻōhiʻa logs are notched and interlocked at the corners, and a second story was added later with shingled walls and a steep metal gable roof. Inside, exposed ʻōhiʻa beams and columns, a winding staircase with chia railings, wooden floors and doors, and a lava rock fireplace give the home its rustic charm.

Tutu's Place - 1929

The Kimi family built this single-story, wood-frame home on a post-and-pier foundation in 1929 for their tūtu (grandmother), giving it the nickname Tutu’s Place. From the road, it looks like a modest cottage, but the home includes a basement at the back and an upper level with a living room, two bedrooms, a bathroom, and a third bedroom converted into a kitchen with a large stained-glass window. Its design draws on the plantation cottage style, featuring a prominent front porch sheltered by a projecting gable roof, which is typical of older Hilo homes.

Kaʻū Plantation Manager's Home - 1932

One of the finest 1930s Craftsman-style homes in Volcano, this house features lava rock pedestals at the porte cochere, curved lava rock railings, clapboard siding, and six-over-six double-hung windows. Exposed rafter ends, a post-and-pier foundation with a lattice skirt, and a lava rock chimney with Art Deco touches highlight its design. A hipped roof with a subtle double pitch, echoed in the porte cochere, and a centered porch with square columns give the home a formal touch. Inside, French doors open to the central living area, with dining and kitchen on one side and bedrooms on the other, all featuring hardwood floors, battened walls and ceilings, and picture rails.

Olaʻa Plantation Manager's Home - 1935

Like the Kaʻū Plantation manager’s vacation home, this tongue-and-groove, hipped-roof house sits on a high post-and-pier foundation with a lattice skirt. A large porte cochere with decorative rafter ends and lava rock pedestals shelters the stepped entrance, framed by lava rock walls with concrete caps. Six-lite casement windows, panel columns, and a cantilevered shed-roof addition on the south side reflect the Craftsman bungalow style common in mid-level plantation housing.

Ludloff Place - 1938

Surrounded by towering tsugi pines and ʻōhiʻa trees, Ludloff Place is a single-story home built in 1938 by the Ludloff family. They were German immigrants who founded the Crescent City Cracker Company in Hilo, famous for Saloon Pilot and Hilo Cream Crackers. While the family’s main Hilo residence was designed by renowned architect Hart Wood, Ludloff Place at Hale ʻŌhiʻa served as their vacation retreat.

ʻŌhiʻa Cottage - 1938

Built in 1938, this simple rectangular house features a lateral gable with an extended shed over the entry lanai and is set far back on the property, creating a spacious front lawn. A ramp was added to the lanai, but the interior of this three-bedroom, one-bath home remains remarkably intact, including the porcelain kitchen sink, panel doors, hardware, and built-in cabinets. The building has typical elements of a Volcano Village summer retreat including tongue-and-groove single-wall construction, original two-over-two double-hung windows, and a brick chimney.

CONTINUE LEARNING

Explore Volcano's Storied Past

Land & Culture

Learn about the deep relationship between people and ʻāina in Native Hawaiian culture as well as past and present efforts to mālama (care for) Volcano's unique ecosystems.

People of Volcano

Meet some of the outstanding people in Volcano's history who influenced and helped shape the Village community into what it is today.

Coming of Age

What was it like to grow up in Volcano? Read this curated collection of anecdotes by Village residents recounting their personal coming-of-age experiences.

GET INVOLVED

Support Our Mission

Volcano Community Foundation is a nonprofit dedicated to preserving and showcasing Volcano's past while working together to meet today's needs and enrich the future of our community.